GOSPEL 1584

Paper, 297 folios, Devik (Erzurum region) in 1584

GOSPEL 1584

Paper, 297 folios, Devik (Erzurum region) in 1584

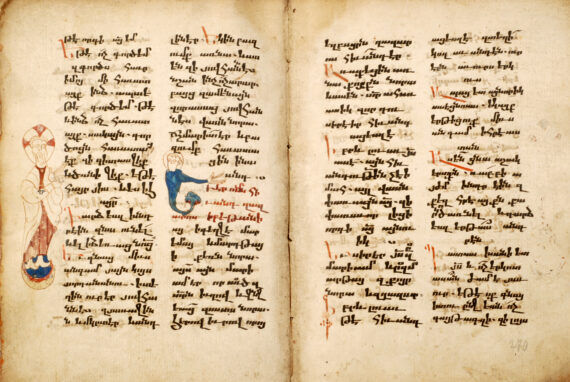

Version intégrale sur la BVMM (IRHT-CNRS)Bolorgir letter on two columns of 22 lines each

Copywriter: Nerses

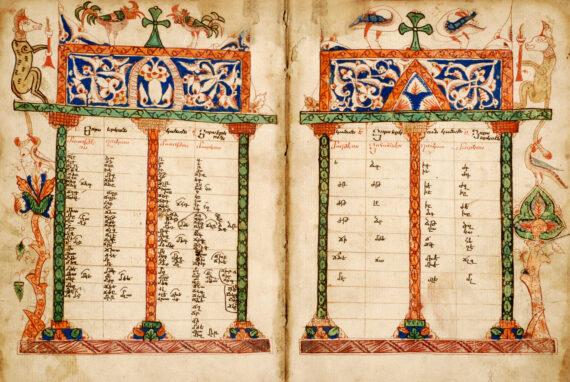

Tables of concordances between the Gospels Matthew-Luke, Matthew-Mark for the first page, Matthew-John, Luke-Mark for the second page. The tables are richly illustrated, with a floral entablature on a blue background, above which rises a cross surrounded by symbolic animals, a rooster and a swan. Three slender columns support the architectural framework; to the left and right outside the framework is a stylized motif of a tree topped by two birds holding in their beaks the tail of a mythological animal. At their feet, a torch closes the chain of a cannon table.

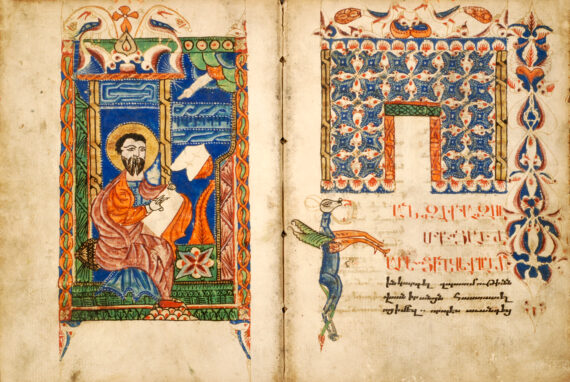

Bright colors were used again in 17th century Armenian miniatures. This small manuscript of the Gospels opens with a letter from Eusebius to Carpianus and tables of canons. It includes the portraits of the Evangelists placed on the first page of their book, as well as some marginal decorations. The first three evangelists are depicted sitting and writing, while John stands and dictates his story to his disciple Prochorus. The eagle, the symbol of John, forms the inscription on the opposite page, below the rectangle decorated with volutes. The artist offers a simplified version of the common iconography of John and Prochorus in Armenian manuscripts: the heavy and static figure of the evangelist is included in the composition, but, nevertheless, he does not turn towards the divine hand which appears above him. Moreover, the backgrounds here are very different from those more familiar, evoking the Cave of the Apocalypse on the island of Patmos: the rocky scree is reduced to simple flat areas with jagged outlines, and the architectural elements are reduced to a few laconic forms.

The artist, probably a copyist, takes the graphic and schematic style of his predecessors to extremes, as seen in a gospel manuscript transcribed at Yerznka, in the same region, nearly a century earlier, in 1488. The Paris manuscript, for its part, acknowledges the oriental taste in the choice of colors, which resembles the modern Ottoman palette and the Armenian pottery produced since the early 17th century in Kutahya.The artist combines a strong and firm line with vivid colours, not without a certain skill, despite the simplicity of the forms, the apparent naivety of the composition and the relatively crude appearance of the book as a whole. The portraits of the Evangelists also bear an unmistakable resemblance to those of the Matenadaran Gospel, also copied in the Karin (Erzurum) region in 1587. Both manuscripts were made in humble villages. The copyist of the 1584 manuscript clearly indicates in the colophon that he did his work in the “village” of Devik, and the same term refers to the village of Salajor in the 1587 colophon. These two gospels testify to a real rural dynamism in Anatolia and, in their own way, foreshadow a revival in the production of painted manuscripts in the seventeenth century.

Origin: Unknown. Former collection of Nurhan Fringian.

Bibliography: Catalogue of the Musée d’Armes de France, 1989.

Paris, Musée Armée de France, Nourhan Fringian Foundation.

Ioanna Rapti

cf. Armenia Sacra, p. 389. Editions Somogy/Musée du Louvre 2007.

In the 10th century, but especially in the early 13th century, a capital letter would be accompanied by a lower case or bolorgir, which was easier to write and took up less space. Paper became available alongside parchment from the end of the 10th century. It was at this time that the Bible began to be copied into a single compilation. This script was used until the 16th century, and continued to exist until the 19th century. The erkatagir, the first form of writing in the 5th century, was then used as the capital letter for the bolorgir, which remained the main script.

In the 10th century, but especially in the early 13th century, a capital letter would be accompanied by a lower case or bolorgir, which was easier to write and took up less space. Paper became available alongside parchment from the end of the 10th century. It was at this time that the Bible began to be copied into a single compilation. This script was used until the 16th century, and continued to exist until the 19th century. The erkatagir, the first form of writing in the 5th century, was then used as the capital letter for the bolorgir, which remained the main script.

In Armenia, the art of books is linked to the invention of writing. Until the 5th century AD, the inhabitants of the Armenian plateau had successively used the cuneiform script (Urartu), and later, with the various conquests, Aramaic (the Persian period), Greek (the Hellenistic and Parthian period) and Latin characters (under Roman domination).

Driven by the need to have a specific writing adapted to the language, around the year 405, an Armenian monk, Mesrop Mashtots, invented an alphabet composed of thirty-six letters or graphemes corresponding to the thirty-six phonemes of the oral language used in the 5th century.

The most widely distributed and recognized book in this Christian nation was the first to be transcribed: The Bible.

This allowed the many copyists in monasteries to learn the alphabet, and they acted as network for disseminating Christianity, and thereby strengthening Armenian identity. This transmission of a culture and a religion made it possible for the identity of a civilisation remain intact despite the vicissitudes of history.

The texts were at first, for the most part, religious, biblical (The Bible—Gospels) or liturgical (Lectionaries—Hymnaries—Psalms—Homiliaries, etc.).

From the end of the 9th century, there was an increase in the amount of manuscript works produced, propagating the faith of a people through this fundamental medium which is writing: it is the union of the written word and religion that allowed this people to survive, despite the lack of an organised state.

To embellish the written word, painters assisted the scribes, and it is in books that we find the best expression of Armenian pictorial art.

The Armenian book was printed in 1511, but manuscripts had such a predominant role that, unlike other countries, book printing in Armenia did not fully develop until the 18th century and it was not until the 19th century that it reached the stage where it could actually replace the work performed by hand.