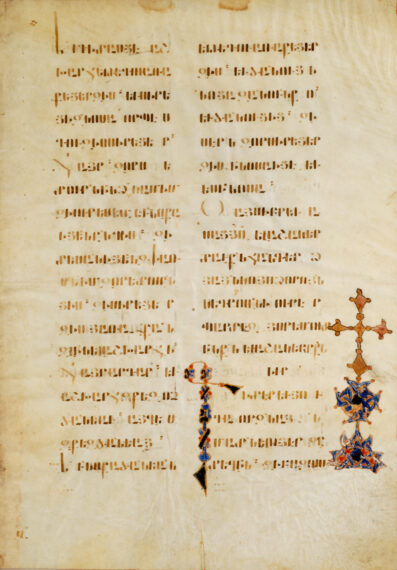

GOSPEL ACCORDING TO SAINT JOHN

Fragment of a manuscript. Parchment.

11th century.

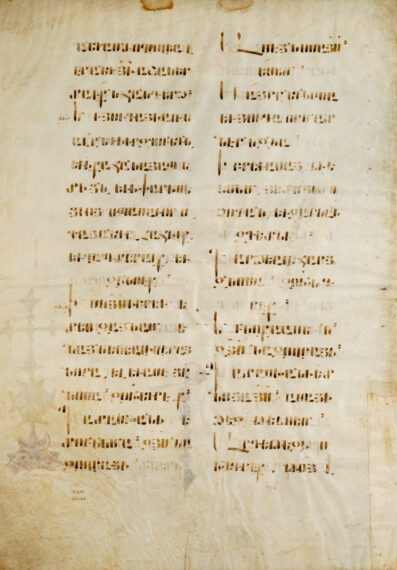

Fragment of a manuscript. Parchment. 11th century.

GOSPEL ACCORDING TO SAINT JOHN

Fragment of a manuscript. Parchment.

11th century.

Fragment of a manuscript. Parchment. 11th century.

It is an excerpt from the Gospel of St. John. It begins with verse 23 of chapter 17 and ends, on the reverse, with verse 8 of chapter 18.

Written in erkatagir in two columns of 19 lines each, the area of the inscription is 245mm x 155mm.

Note that at 17mm from the left edge of the page we can notice 19 vertical punctures (more prominent towards the top), designed to mark up the 19 lines. The middle of the page is marked by a dot on the border.

At the end of some lines, one or two spaced letters indicate the justification of the columns. The rounded script of erkatagir dates back to the second half of the 11th century. The letters are 5-6mm, the initial capital letters of the verses are 15 mm. The text includes punctuation and intonation marks. The dark brown ink is lighter in some places. The title “Y[isu]S” [Jesus] is in abbreviated form and highlighted with an abbreviation mark. The nomina sacra as well as the first line of chapter 18 on the obverse are all written in gold ink. Section marks in written numbers are seen in the outer and inner margins and in between columns. The section headings of the canons are in the lower margins.

According to the ancient rubric of Armenian manuscripts, chapter 18 (facing) begins with the verse, “Now Judas, who betrayed him, knew the place.” (now John 18:2). (now Jn 18:2), marked with the ornate initial “G” [the third letter of Armenian alphabet] and the use of gold ink for the first line. After the changing of rubric in the thirteenth century, this verse became the second of chapter 18.

The ornamented initial “G” (height 77mm) is formed by a narrow stem that widens into triangles at the ends. Blue, red and darkened green crucibles, complemented by gold, are intertwined with each other. In contrast, on the outer margin, a gold cross composed of alternating rhombuses and spheres rests on a base composed of two elements, rounded and triangular at the base. Both are decorated with motifs dominated by bright blues and reds accentuated by gold.

Edda Vardanyan

In Armenia, the art of books is linked to the invention of writing. Until the 5th century AD, the inhabitants of the Armenian plateau had successively used the cuneiform script (Urartu), and later, with the various conquests, Aramaic (the Persian period), Greek (the Hellenistic and Parthian period) and Latin characters (under Roman domination).

Driven by the need to have a specific writing adapted to the language, around the year 405, an Armenian monk, Mesrop Mashtots, invented an alphabet composed of thirty-six letters or graphemes corresponding to the thirty-six phonemes of the oral language used in the 5th century.

The most widely distributed and recognized book in this Christian nation was the first to be transcribed: The Bible.

This allowed the many copyists in monasteries to learn the alphabet, and they acted as network for disseminating Christianity, and thereby strengthening Armenian identity. This transmission of a culture and a religion made it possible for the identity of a civilisation remain intact despite the vicissitudes of history.

The texts were at first, for the most part, religious, biblical (The Bible—Gospels) or liturgical (Lectionaries—Hymnaries—Psalms—Homiliaries, etc.).

From the end of the 9th century, there was an increase in the amount of manuscript works produced, propagating the faith of a people through this fundamental medium which is writing: it is the union of the written word and religion that allowed this people to survive, despite the lack of an organised state.

To embellish the written word, painters assisted the scribes, and it is in books that we find the best expression of Armenian pictorial art.

The Armenian book was printed in 1511, but manuscripts had such a predominant role that, unlike other countries, book printing in Armenia did not fully develop until the 18th century and it was not until the 19th century that it reached the stage where it could actually replace the work performed by hand.