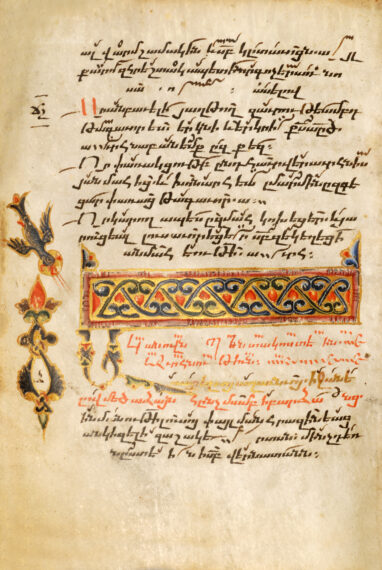

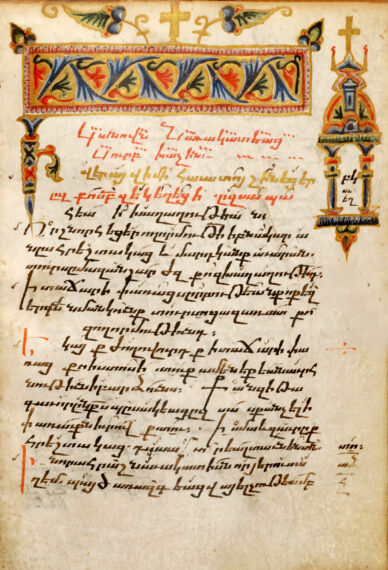

Hymnal of 1332

Parchment, dated 1332 in the colophon

Hymnal of 1332

Parchment, dated 1332 in the colophon

Version intégrale sur la BVMM (IRHT-CNRS)In Armenian: Sharaknots.

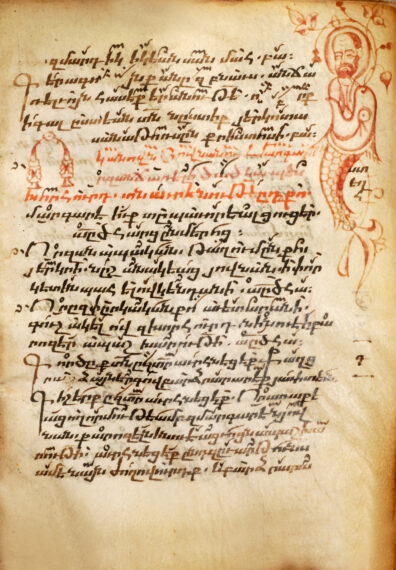

Text referring to Jonah and the whale.

The title written in red ink announces the Canon of the prophet Jonah, planned for its commemoration.

The text is accompanied by the marginal illumination that depict Jonah emerging from the belly of the whale. The iconography of the prophet’s rescue is highlighted by a flowering of stylised leaves forming an arc above his head. It alludes to the plant that God made grow to shade Jonah near the gates of Ninive after his rescue (Jonah IV, 6). At the same time, the whole image under the name of the “sign of Jonah” is a symbol of the Resurrection of Christ.

In fact, in the Armenian illustrated gospels, one can see the same marginal composition in connection with the text of the Gospel according to Matthew (XII, 38-40). In this passage, the scribes and Pharisees ask Jesus for a miracle that could serve as a sign of his divine mission. Jesus answers that they will not be given any other sign than that of Jonah. The link would be suggested by the expression “three days and three nights:” “As Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of a great fish, so the Son of Man will be three days and three nights in the bosom of the earth.”

It is this symbolic sign “of Jonah,” which we see here, next to the Hymn whose text begins with an evocation of the above-mentioned passage from Matthew and which then draws a parallel between the story of Jonah and the Resurrection of Christ.

Edda Vardanyan

In Armenia, the art of books is linked to the invention of writing. Until the 5th century AD, the inhabitants of the Armenian plateau had successively used the cuneiform script (Urartu), and later, with the various conquests, Aramaic (the Persian period), Greek (the Hellenistic and Parthian period) and Latin characters (under Roman domination).

Driven by the need to have a specific writing adapted to the language, around the year 405, an Armenian monk, Mesrop Mashtots, invented an alphabet composed of thirty-six letters or graphemes corresponding to the thirty-six phonemes of the oral language used in the 5th century.

The most widely distributed and recognized book in this Christian nation was the first to be transcribed: The Bible.

This allowed the many copyists in monasteries to learn the alphabet, and they acted as network for disseminating Christianity, and thereby strengthening Armenian identity. This transmission of a culture and a religion made it possible for the identity of a civilisation remain intact despite the vicissitudes of history.

The texts were at first, for the most part, religious, biblical (The Bible—Gospels) or liturgical (Lectionaries—Hymnaries—Psalms—Homiliaries, etc.).

From the end of the 9th century, there was an increase in the amount of manuscript works produced, propagating the faith of a people through this fundamental medium which is writing: it is the union of the written word and religion that allowed this people to survive, despite the lack of an organised state.

To embellish the written word, painters assisted the scribes, and it is in books that we find the best expression of Armenian pictorial art.

The Armenian book was printed in 1511, but manuscripts had such a predominant role that, unlike other countries, book printing in Armenia did not fully develop until the 18th century and it was not until the 19th century that it reached the stage where it could actually replace the work performed by hand.

In the first half of the 8th century B.C. in the Northern Kingdom of Israel, the prophet Jonah was given a mission by God to bring the message of God to the depraved people of Nineveh, in Mesopotamia. But he did not obey promptly and fleed from the presence of the Lord on a ship bound for Spain. During the crossing, there was a huge storm. The sailors took fright and implored God to save them. The captain then suspected that Jonas was the cause of this storm. It was decided that lots should be drawn to identify the culprit. Jonah was designated and thrown overboard. The storm calmed immediately. Jonah was swallowed by a large fish, which might have been a whale. In the belly of the animal he prayed to the Lord for three days. He finally realised that he must get out of this situation and save the city of Nineveh from chaos.

God heard him, the whale vomited Jonah out onto the shores of Nineveh where he went and finally persuaded the inhabitants of the city to repent.

The tale of Jonas is marvellously recounted, but going beyond that, it necessary to understand the relationship between the Old and New Testaments: there is a connection to be made between the three days and nights that Jonas spent in prayer in the belly of the whale, and the three days spent “in the belly of the earth” by Jesus before His resurrection.

Jonah and Jesus followed the will of God.