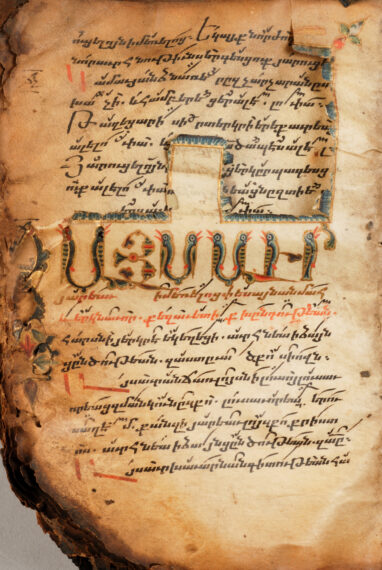

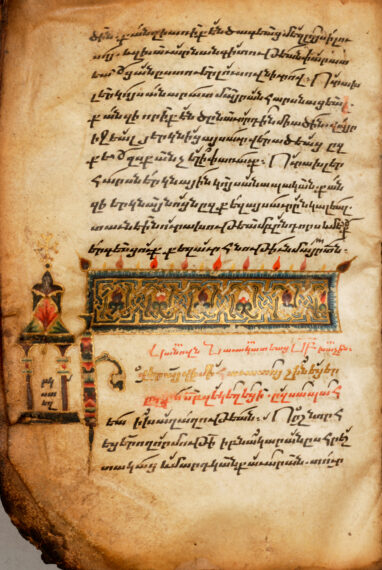

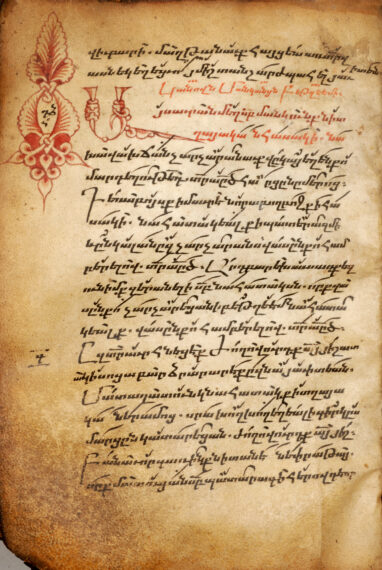

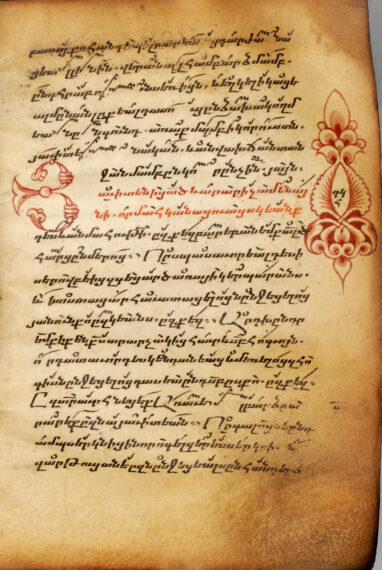

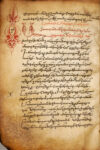

Hymnal of 1342

Parchment, dated 1342 in the colophon

Hymnal of 1342

Parchment, dated 1342 in the colophon

Version intégrale sur la BVMM (IRHT-CNRS)Manuscript saved from fire, illumination “cannibalized.” Sharaknots in bolorgir script. Transcribed by Nerses Kegenz, at Hulaivank Monastery, at the request of the Arakel.

In the 10th century, but especially in the early 13th century, a capital letter would be accompanied by a lower case or bolorgir, which was easier to write and took up less space. Paper became available alongside parchment from the end of the 10th century. It was at this time that the Bible began to be copied into a single compilation. This script was used until the 16th century, and continued to exist until the 19th century. The erkatagir, the first form of writing in the 5th century, was then used as the capital letter for the bolorgir, which remained the main script.

In the 10th century, but especially in the early 13th century, a capital letter would be accompanied by a lower case or bolorgir, which was easier to write and took up less space. Paper became available alongside parchment from the end of the 10th century. It was at this time that the Bible began to be copied into a single compilation. This script was used until the 16th century, and continued to exist until the 19th century. The erkatagir, the first form of writing in the 5th century, was then used as the capital letter for the bolorgir, which remained the main script.

In Armenia, the art of books is linked to the invention of writing. Until the 5th century AD, the inhabitants of the Armenian plateau had successively used the cuneiform script (Urartu), and later, with the various conquests, Aramaic (the Persian period), Greek (the Hellenistic and Parthian period) and Latin characters (under Roman domination).

Driven by the need to have a specific writing adapted to the language, around the year 405, an Armenian monk, Mesrop Mashtots, invented an alphabet composed of thirty-six letters or graphemes corresponding to the thirty-six phonemes of the oral language used in the 5th century.

The most widely distributed and recognized book in this Christian nation was the first to be transcribed: The Bible.

This allowed the many copyists in monasteries to learn the alphabet, and they acted as network for disseminating Christianity, and thereby strengthening Armenian identity. This transmission of a culture and a religion made it possible for the identity of a civilisation remain intact despite the vicissitudes of history.

The texts were at first, for the most part, religious, biblical (The Bible—Gospels) or liturgical (Lectionaries—Hymnaries—Psalms—Homiliaries, etc.).

From the end of the 9th century, there was an increase in the amount of manuscript works produced, propagating the faith of a people through this fundamental medium which is writing: it is the union of the written word and religion that allowed this people to survive, despite the lack of an organised state.

To embellish the written word, painters assisted the scribes, and it is in books that we find the best expression of Armenian pictorial art.

The Armenian book was printed in 1511, but manuscripts had such a predominant role that, unlike other countries, book printing in Armenia did not fully develop until the 18th century and it was not until the 19th century that it reached the stage where it could actually replace the work performed by hand.