LITURGICAL HYMN BOOK

Manuscript on paper, 372ff, made at Çüngüş – 1591.

LITURGICAL HYMN BOOK

Manuscript on paper, 372ff, made at Çüngüş – 1591.

Version intégrale sur la BVMM (IRHT-CNRS)A COLLECTION OF LITURGICAL SONGS

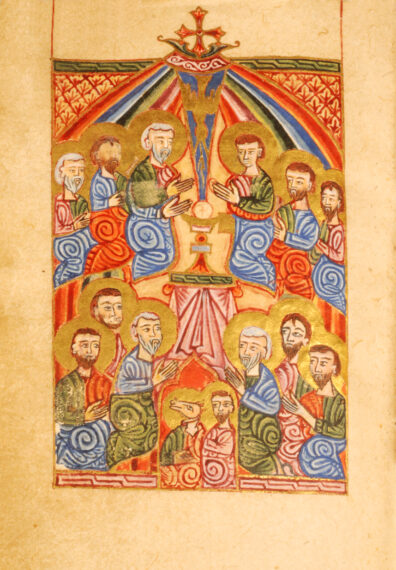

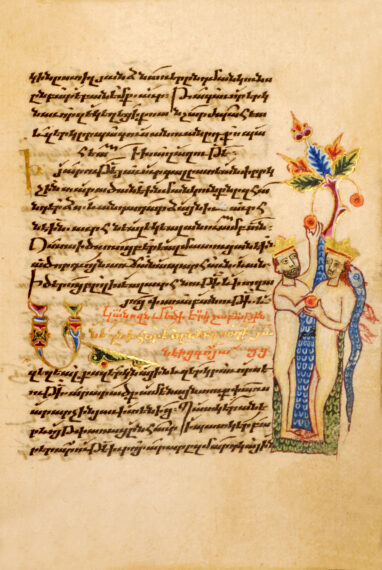

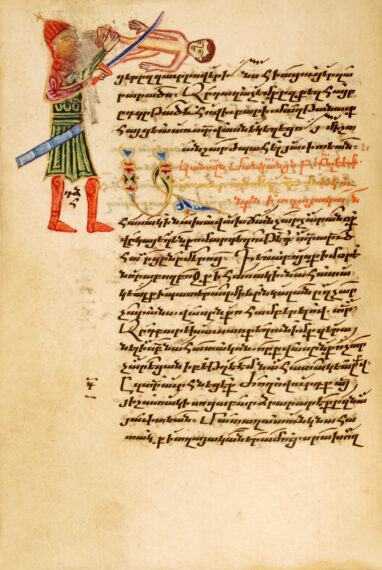

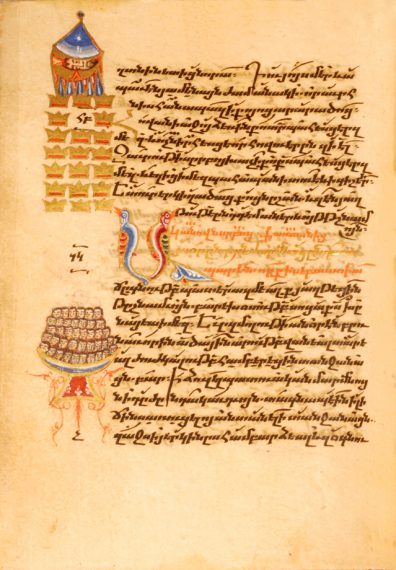

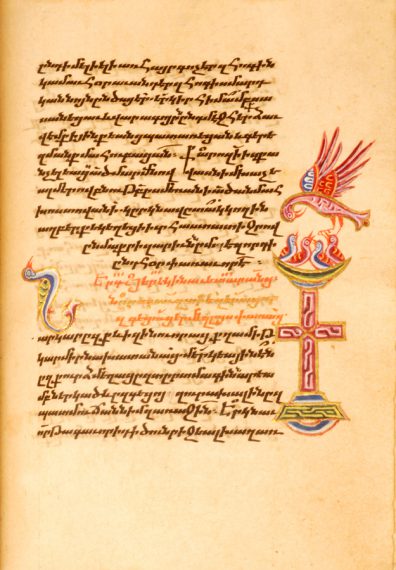

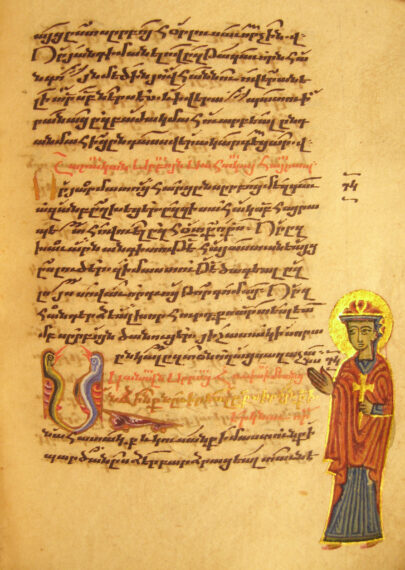

This collection of festive liturgical hymns (in Armenian–Ergaran) was transcribed in 1591, as indicated in the colophon, at Küngüs, a bishopric located between Diarbekir and Malatya, in southeast of modern Turkey. The small format of the manuscript indicates that it was intended for private use, but it is notable for the elaborate decoration and the abundance of painted ornaments illuminated with gold. Each major section, which in principle follows the order of the liturgical calendar, is marked with gold and colored vignettes. Each hymn begins with an ornate letter followed by a line of gold text, and the titles and second line are in red. The collection includes two full-page paintings, of Joachim and Anne, addressing the Nativity of the Virgin Mary and Pentecost, prefacing the corresponding ode. Finally, some thirty marginal miniatures accompany the songs, placed at the beginning and serving as handy visual cues. Some recall stories, such as those of Adam and Eve, while others represent the saints commemorated, such as St. Joachim and Anna.

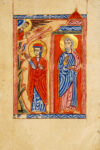

The Armenian hymns open with the Canon of the Birth of the Virgin Mary: Canon of the Magnificat and Wonderful Birth of Our Lady of the Virgin by? Joachim and Anna. Opposite this canon is a full-page illustration of Mary’s parents, Joachim and Anna (folio 3v°).

While the hymn is devoted to the glorification of the Virgin Mary, the illumination shows the prayer of Anna, an episode taken from the apocryphal Gospel of the Childhood of Christ, or the Protoevangelium of James the Armenian translation of which is from a very early period. According to the Armenian version, Anna, seeing a nest of sparrows in the branches of a laurel tree, is distressed in her garden because of its barrenness and cries out to the Lord. Joachim, in turn, prays in the desert where he is with his flock. He asks God to grant him a child as He did for his ancestor, the patriarch Abraham. An angel appears to Joachim and then to Anna and tells them that the Lord will answer their prayers. The couple, each warned in turn, joyfully meet at the gate of Jerusalem.

In our illumination, Anna is praying in her garden. Behind her stands Joachim framed architecturally. Western and Byzantine art has never depicted Joachim with Anna at the moment of her prayer. As a rule, in narrative cycles devoted to the life of the Virgin, they are depicted separately or when they meet.

In Armenian art, however, the depiction of Mary’s parents is attributed to the Hymnarians. And since both Joachim and Anna are mentioned in the title of the canon, they are always together in the same composition. The angel in the upper corner, making a gesture of blessing, shows the divine favor shown to the couple, and the building framing Joachim recalls the couple’s meeting at the city gate.

This iconographic formula has become a classic illustration of the Hymn in Armenia and is found in manuscripts from the 15th to the 17th century.

Edda Vardanian.

In Armenia, the art of books is linked to the invention of writing. Until the 5th century AD, the inhabitants of the Armenian plateau had successively used the cuneiform script (Urartu), and later, with the various conquests, Aramaic (the Persian period), Greek (the Hellenistic and Parthian period) and Latin characters (under Roman domination).

Driven by the need to have a specific writing adapted to the language, around the year 405, an Armenian monk, Mesrop Mashtots, invented an alphabet composed of thirty-six letters or graphemes corresponding to the thirty-six phonemes of the oral language used in the 5th century.

The most widely distributed and recognized book in this Christian nation was the first to be transcribed: The Bible.

This allowed the many copyists in monasteries to learn the alphabet, and they acted as network for disseminating Christianity, and thereby strengthening Armenian identity. This transmission of a culture and a religion made it possible for the identity of a civilisation remain intact despite the vicissitudes of history.

The texts were at first, for the most part, religious, biblical (The Bible—Gospels) or liturgical (Lectionaries—Hymnaries—Psalms—Homiliaries, etc.).

From the end of the 9th century, there was an increase in the amount of manuscript works produced, propagating the faith of a people through this fundamental medium which is writing: it is the union of the written word and religion that allowed this people to survive, despite the lack of an organised state.

To embellish the written word, painters assisted the scribes, and it is in books that we find the best expression of Armenian pictorial art.

The Armenian book was printed in 1511, but manuscripts had such a predominant role that, unlike other countries, book printing in Armenia did not fully develop until the 18th century and it was not until the 19th century that it reached the stage where it could actually replace the work performed by hand.

The canonical Gospels of the New Testament do not directly mention the parents of the Virgin Mary. The names of Mary’s parents have been passed down through Christian tradition: Joachim (“God grants”) and Anne (“Grace—the gracious one”), as well as the location of their house, in Jerusalem, near the temple. The story of Joachim and Anne appears in the apocryphal Gospel of James, in partly scholarly and partly ordinary text (see the “Protevanelium of James,” 1–4; text in Christian Apocryphal Writings, directed of F. BOVON and P. GEOLTRAIN, La Pléiade, Paris 1997, p. 82–85). This text was probably written around the year 150 AD in Alexandria.

Anne and Joachim were from the tribe of Judah and of the royal line of David. They were rich and owned large herds. They lived a holy life: Joachim is described as a pious man who regularly gave to the poor and to the temple. Despite their fervent prayers, however, they sadly had no children. For the Jews, this was the worst of all curses, and led to Joachim offering to the temple being rejected: as his wife was sterile, the High Priest rejected Joachim and his sacrifice, his wife’s infertility being interpreted as a sign of God’s displeasure. This greatly distressed Joachim who then withdrew to the desert where he fasted and did penance for forty days and forty nights, saying to himself: “I shall not go down either for food or for drink until the Lord my God visits me; prayer shall be my food and drink.”

According to the Apocrypha, Anne also was greatly distressed, and called upon the Master, saying: “God of my fathers, bless me and hear my prayer, just as you blessed our mother Sarah and gave her a son, Isaac.”

Angels appear to Joachim and Anne to promise them that they would have a child. Anne saw an angel of the Lord standing before her, saying: “Anne, Anne, the Lord God has heard your prayer. You shall conceive and bear children, and your descendants shall be spoken of throughout the world.” And Anne said: “As the Lord God lives, if I beget either male or female, I will bring it as an offering to the Lord my God, and it will minister to Him for all the days of its life.”

At the same time, an angel of the Lord had come down to Joachim, saying: “Joachim, Joachim, the Lord God has heard your prayer. Go down hence. For behold, your wife Anne has conceived.” Joachim returned to Jerusalem, and near the Golden Gate, he found Anne whom he “embraced,” their prayers were heard: Mary, the mother of God, was conceived and her conception is immaculate.

The narratives about Joachim and Anne were included in the Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine. They are much represented in Christian art, often by a graceful image of marital love, immortalizing their kiss when they learned that Mary had been conceived.