ROULEAU DE PRIÈRE

Papier, XVIIe XVIIIe siècle. Empire ottoman. Fragment

ROULEAU DE PRIÈRE

Papier, XVIIe XVIIIe siècle. Empire ottoman. Fragment

Ecriture notrgir

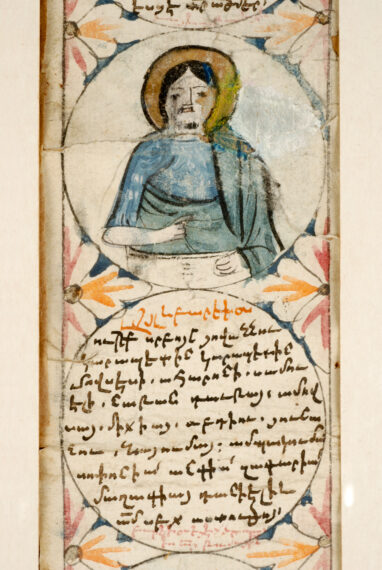

Le fragment contient d’abord une prière de protection suivie d’invocations inscrites dans des médaillons et adressées aux Saints Etienne, Jean-Baptiste et Grégoire l’Illuminateur, dont les potraits figurent au-dessus de chaque prière.

Leur iconographie rappelle celle des manuscrits tardifs, notamment des synaxaires réalisés à Constantinople .

Influencées par l’art post-byzantin et occidental, ces images sont simples et sommaires. L’avant dernier texte en bas de l’image, une prière de protection adressée à la Trinité, est inscrit dans trois médaillons et précédé de l’image du Christ enfant dans un calice, tenant deux rameaux fleuris de ses bras écartés.

La partie inferieure offre une illustration succincte du sacrifice d’Abraham. En-dessous, le texte correspondant est disposé en losanges selon une formule habituelle pour ce passage : les lignes descendantes des versets bibliques s’imbriquent avec celle ascendantes d’une prière qui se réfère aux symboles de la Passion (Feydit, 1986, p.10).

Provenance : ancienne collection Nourhan Fringhian.

Bibliographie : catalogue du Musée arménien de France, 1989.

Paris, Musée arménien de France, fondation Nourhan Fringhian.

Ioanna Rapti

cf Armenia Sacra, p. 32. Editions Somogy/Musée du Louvre 2007.

In Armenia, the art of books is linked to the invention of writing. Until the 5th century AD, the inhabitants of the Armenian plateau had successively used the cuneiform script (Urartu), and later, with the various conquests, Aramaic (the Persian period), Greek (the Hellenistic and Parthian period) and Latin characters (under Roman domination).

Driven by the need to have a specific writing adapted to the language, around the year 405, an Armenian monk, Mesrop Mashtots, invented an alphabet composed of thirty-six letters or graphemes corresponding to the thirty-six phonemes of the oral language used in the 5th century.

The most widely distributed and recognized book in this Christian nation was the first to be transcribed: The Bible.

This allowed the many copyists in monasteries to learn the alphabet, and they acted as network for disseminating Christianity, and thereby strengthening Armenian identity. This transmission of a culture and a religion made it possible for the identity of a civilisation remain intact despite the vicissitudes of history.

The texts were at first, for the most part, religious, biblical (The Bible—Gospels) or liturgical (Lectionaries—Hymnaries—Psalms—Homiliaries, etc.).

From the end of the 9th century, there was an increase in the amount of manuscript works produced, propagating the faith of a people through this fundamental medium which is writing: it is the union of the written word and religion that allowed this people to survive, despite the lack of an organised state.

To embellish the written word, painters assisted the scribes, and it is in books that we find the best expression of Armenian pictorial art.

The Armenian book was printed in 1511, but manuscripts had such a predominant role that, unlike other countries, book printing in Armenia did not fully develop until the 18th century and it was not until the 19th century that it reached the stage where it could actually replace the work performed by hand.